Malachi to Christ

HEROD

Malachi to Christ

HEROD

Roman Period (160 B.C. to 70 A.D.)

Pompey the Great

The civil war between Hyrcanus and Aristobulus was interrupted by the appearance of a new actor on the scene. Fresh from his beneficent war against the pirates who infested the Mediterranean, from his more brilliant victory over the last of the mighty potentates of Asia, Mithridates, the marvelous king of Pontus – Pompey the Great, with all his fame in its first and yet untarnished splendor, moved toward Palestine. At Antioch he dissolved the last remnant of the Syrian monarchy on the ground that it was an insufficient rampart against the inroads of the Armenians and Parthians from the Far East. He then advanced to Damascus. It was a memorable year in Roman history for the consulship of Cicero, the conspiracy of Catiline, and the birth of Augustus. It was not less memorable for the meeting which, in the oldest of Syrian cities, took place between the illustrious Roman and the two aspirants for the Jewish Monarchy. The rivals were attracted by the enormous prestige of the man, who, having revived the terror of the Roman name in Africa, and crushed the most formidable insurrections in Spain and Italy, had now vanquished the kings of Asia. They were led even more by his widespread fame for humanity and moderation which made him the arbiter of the contending princes of the East. No personage of such renown and authority had been seen by any Israelite eyes since the meeting of Alexander and Jaddua. Indeed, there was something even in the outward appearance of the famous Roman which recalled the aspect of the famous Greek. The august expression gracefully blended with the bloom of his manly prime and singularly engaging manners – his hair smoothly turned back from his brow, the liquid glance of his eyes resembling the traditional likeness of Alexander (it is thought that in his triumph he wore the actual "chlamys" or military cloak of Alexander). Standing before the colossal statues of Pompey, that gentler figure in the Villa Castellazzo near Milan, or the commanding form in Rome's Spada Palace at whose base great Caesar fell (wonderfully preserved through the vicissitudes of neglect, revolution, and siege), modern travelers cannot escape some notion of the mingled awe and affection which he inspired and which the Jewish princes must have felt when they bowed before him. It was in such interviews that he must have conspicuously shone – it was said that "when he bestowed it was with delicacy, when he received it was with dignity; and though he knew not how to restrain the offences of those whom he employed, yet he gave so gracious a reception to those who came to complain that they went away satisfied".

Aristobulus II

On one side was Aristobulus, the gallant King whose high spirit called forth at every turn the reluctant admiration of the cynical historian, displaying itself even in the very act of pleading his cause, blazing with every conceivable mark of royalty, surrounded by his young nobles, conspicuous with their scarlet mantles, trappings, and profusion of clustering locks. At the feet of the victorious general he laid a gift so magnificent that long afterwards it was regarded as one of the wonders of the Capitol – the emblem of his nation, a golden vine growing out of a "Pleasaunce" and bearing the name of Alexander, his father. From all this barbaric pomp, which to the yet uncorrupted taste of the proud Roman citizen produced no other feeling than disgust, the conqueror turned to the other candidate.

Hyrcanus II

Hyrcanus was as insignificant as Aristobulus was commanding in character and appearance – then, as always, a tool in the hands of others. With him were the heads of the great party who, in their hostility to the Sadducaic and Pontifical elements represented by the rival brother, did not scruple to insinuate against him the charge that he was not a genuine friend of Rome. And with them, inspiring and guiding all, was the man destined to inaugurate for the Jewish nation the last phase of its existence. When John Hyrcanus subdued the Edomites, and incorporated them into the Jewish Church, little did he dream that he was nourishing the evil genius that would be the ruin of his house.

Antipater

The son of the first native governor of the conquered Idumaea, who himself succeeded to his father's post, was Antipater or Antipas, father of Herod. With a craft more like that of the supplanter Jacob than the generosity of his own ancestor Esau, he perceived that his chance of retaining his position would be imperilled by the independent spirit of the younger brother, and might be secured by making himself the ally and master of the elder. To his persuasions the Roman general lent a willing ear, and Hyrcanus was preferred. Aristobulus surrender his hopes, but not without a struggle. From Damascus he retired to the family fortress, the Alexandreum, commanding the passes into southern Palestine. Pompey followed, and in a fit of desperation after one or two futile parleys, Aristobulus finally broke away from the stronghold, threw himself into Jerusalem, and there defied the conqueror of the East.

Pompey's March to Jericho

The crisis was at once precipitated. Like that of Sennacherib of old, every step of Pompey's advance is noted. But it was by a route which no previous invader had adopted. Instead of following the central thoroughfare by Shechem and Bethel, from the fortress of Alexandreum he plunged into the Jordan valley and encamped beside the ancient city where Joshua had gained his first victory over the Canaanites. It would almost seem as if it was the fame of Jericho which had occasioned this deviation. It was a spot, which, having sunk into deep obscurity, during this latter period revived with a glory peculiar to itself. There is a faint tradition that even as far back as the Persian dominion it had been raised to a rank rivalling, if not exceeding, that of Jerusalem and this equality was henceforth never lost till the fall of both. Long afterwards in the homes of Roman soldiers was preserved the recollection of the magnificent spectacle which burst upon them, when for the first time they found themselves in the midst of the tropical vegetation which even now to some degree, but then transcendently, surrounded the city of Jericho. In the present day not one solitary relic remains of those graceful trees which once were the glory of Palestine. But then the plain was filled with a splendid forest of palms, 'the Palm-grove,' as it was called, three miles broad and eight miles long, interspersed with gardens of balsam, traditionally sprung from the balsam-root that the Queen of Sheba brought to Solomon – so fragrant that the whole forest was scented with them, so valuable that a few years later no richer present could be made to Cleopatra by Antony. The Roman army halted for one night in this green oasis, beside the diamonds of the desert, which still pour forth their clear streams in that sultry valley, but which then were used to feed the spacious reservoirs in which the youths of those days delighted to plunge and frolic in the long days of summer and autumn.

It was an eventful day not only for Palestine. The shades of evening were falling over the encampment. Pompey was taking his usual ride after the march – careering round the soldiers as they were pitching their tents, when couriers were seen advancing from the north at full speed waving on the points of their lances branches of laurel, to indicate some joyful news. The troops gathered round their general, and asked to hear the tidings. At their eager wishes he sprang down from his horse; they extemporized a tribune, hastily constructed of piles of earth and packsaddles which lay upon the ground, and he read aloud the dispatch, which announced the crowning mercy of his Oriental victories – the death of Mithridates his great enemy.

To Jerusalem

Wild was the shout of joy which went up from the army. It was as though ten thousand enemies had fallen. Throughout the camp arose the smoke of thankful sacrifice, and the festivity of banquets rang in every tent. Filled with this sense of triumphant success the army started at break of day for the interior of Judaea, after first occupying the fortresses which commanded that corner of the Jordan valley (perhaps those which were known by the name of foreign mercenaries who manned them) as well as those which guarded the Dead Sea. Thus Pompey advanced in perfect security towards the mysterious and sacred city which no doubt possessed a special attraction for the curiosity of the inquiring Roman. From the north, from the south, from the west, the situation of Jerusalem produces but little effect on the spectator. But, seen from the east (seen from that ridge of Olivet whence, of its conquerors, Pompey alone first beheld it, rising like a magnificent apparition out of the depth and seclusion of its mountain valleys) it must have struck him with all its awe, and, had his generous heart forecast all the miseries of which his coming was the prelude, might have inspired something of that compassion which the very same view, seen from the same spot ninety years later, awakened in One who burst into tears at the sight of Jerusalem and mourned over her fatal blindness to the grandeur of her mission. From this point, Pompey descended and swept round the city to encamp on the level ground at its western side.

Once more Aristobulus ventured into the conqueror's presence; but this time he was seized and chained. Then, within the walls broke out one of those bitter internal conflicts of which Jerusalem has so often been the scene. The Temple was occupied by the patriots, who, even in this extremity, would not abandon their king and country. The Palace and the walls were seized by those who, in passionate devotion to their party, were willing to admit the foreigner.

The bridge between the Palace and the Temple was broken down; the houses round the Temple mount were occupied. Thus, for three months the siege continued. As if to bring out in the strongest relief the Jewish character in this singular crisis, the Sabbath, which, during the last two centuries had played so conspicuous a part in the history of the nation, was turned to account by the Romans in preparing their military engines and approaches, which, even in spite of the example of the first Asmonean, were held by the besieged not to be sufficient cause for a breach of the sacred rest. It may be that it was one of the instances in which the strict adherence of the Sadducees to the letter of the Law outran the zeal of their Pharisaic opponents. However occasioned, the Jewish and Gentile historians concur in representing this enforced inactivity as the cause of the capture of the city. It was the greatest sacrifice that the Sabbatarian principle ever exacted or received.

Capture of the City (63 B.C.)

At last the assault was made. So big with fate did the event appear that the names of the officers who stormed the breach were all remembered. The first was Cornelius Faustus, son of the dictator Sylla; and, immediately following, the centurions Furius and Fabius. A general massacre ensued, in which it is said that 12,000 perished. So deep was the horror and despair that many sprang over the precipitous cliffs. Others died in the flames of the houses, which, like the Russians at Moscow, they themselves set on fire. But the most memorable scene was that which the Temple itself presented. On that solemn festival, which the enemy had chosen for their attack, the Priests were all engaged in their sacred duties. The sacerdotal order of Jerusalem awaited their doom with a dignity as unshaken as that which the Roman senators showed when in curule chairs they confronted the Gaulish invaders three centuries before. They were robed in black sackcloth, which on days of lamentation superseded their white garments, and sat immovable in their seats round the Temple court as if they were caught in a net, till they fell under the hands of their assailants.

Entrance into the Holy of Holies

And now came the final outrage – that which in Nebuchadnezzar's siege had been prevented by the general conflagration, that which Alexander forbore, that from which Ptolemy the Fourth had as it was supposed been deterred by a preternatural visitation, that on which even Antiochus Epiphanes had only partially ventured. The final outrage was now to be accomplished by the gentlest and most virtuous soldier of the Western world. He was irresistibly drawn on by the same grand curiosity which had always mingled with his love of fame and conquest, which inspired him with the passion for seeing with his own eyes the shores of distant seas, i.e., the Atlantic, the Caspian, and the Indian Ocean, which Lucan has in part placed in the mouth of his rival in ascribing to him for his last great ambition the discovery of the sources of the Nile.

He passed into the nave (so to speak) of the Temple, where none but Priests might enter. There he saw the golden table, sacred candlestick (which Judas Maccabaeus had restored), the censers, piles of incense, and the accumulated offerings of gold from all the Jewish settlements. But he touched and took nothing – a moderation so rare in those days that both Cicero at the time and Josephus in the next century commended it as an act of almost superhuman virtue. He arrived at the vast curtain which hung across the Holy of Holies, into which none but the High Priest could enter on one day in the year, perhaps the very day on which Pompey found himself there. No doubt, he had often wondered what that dark cavernous recess could contain. Who or what was the God of the Jews was a question commonly discussed at philosophical entertainments both before and afterwards. When the quarrel between the two Jewish rivals came to the ears of the Greeks and Romans, the question immediately arose as to the Divinity that these Princes both worshipped. Sometimes a rumor reached them that it was an ass's head; sometimes the venerable lawgiver wrapped in his long beard and wild hair; sometimes, perhaps, the sacred emblems which once were there, but had been lost in the Babylonian invasion; sometimes some god or goddess in human form like those who sat enthroned behind the altars of the Parthenon or the Capitol. He drew the veil aside. Nothing more forcibly shows the immense superiority of the Jewish worship to any which then existed on the earth than the shock of surprise occasioned by this one glimpse of the exterior world into that unknown and mysterious chamber. There was no 'thing'. Instead of all the fabled figures of which he had heard or read he found only a shrine, as it seemed to him, without a God – a sanctuary without an image.

Doubtless the Grecian philosophers had at times conceived an idea of the Divinity as spiritual; doubtless the Etruscan priests had established a ritual as stately; but what neither philosopher nor priest had conceived before was the idea of a worship (national, intense, elaborate) of which the very essence was that the Deity receiving it was invisible. Often, even in Christian times, has Pompey's surprise been repeated: often it has been said that without a localizing, dramatizing, materializing representation of the Unseen, all worship would be impossible. The reply which he must, at least for the moment, have made to himself was that contrary to all expectation he had there found it possible.

It was natural that so rude a shock to the scruples of the Jews as Pompey's entrance into the Holy of Holies should be long resented, that when the deadly strife began between the two foremost men of the Roman world they should join Caesar, with all his vices, against Pompey, with all his virtues. It was natural, though less excusable, that even Christian writers should represent the calamities which afterwards overtook the hero of the East as a Divine vengeance for this intrusion. Yet, surely, if ever in those times such intrusion were deemed admissible, it was to be forgiven in one whose clean hands and pure heart, compared with most of the contemporary chiefs, David would have regarded as no disqualification for a dweller on God's Holy Hill – in one, through whose deep and serious insight, even if only for a moment, into the significance of that vacant shrine, the Gentile world received a thrill of sacred awe which it never lost and the Christian world may receive a lesson which it has often sorely needed.

On the next day, with the same highbred courtesy that marked all his dealings, like that which distinguished even the Pilate and Felix of a later day, he gave orders to purify the Temple from the contamination which he knew his presence there must have occasioned, and invested with the Pontificate the unfortunate Hyrcanus, destined (if we may here thus apply the description of another claimant of a shadowy sceptre) to thirty years of exile and wandering, of vain projects, of honors more galling than insults, and of hopes such as make the heart sick.

Conquest of Palestine

With the rule of a master he took command of the whole country. The chiefs of the insurgents were beheaded. The Jewish race was once more confined within the narrow limits of Judah, which henceforth takes the name of Judaea. Gadara was made over to its townsman, Demetrius, Pompey's favorite freedman. To all the outlying towns on the coast and beyond the Jordan which Simon had subdued, he restored their independence. The ancient capital of Samaria, which John Hyrcanus had destroyed, was rebuilt by Gabinius and bore his name until it took the title from a far greater Roman, which through all its subsequent changes it has never lost, in Greek Sebaste, in Latin Augusta – the city of Augustus. The unity of government was broken into five separate councils, which were to sit with equal power at Jerusalem, Gadara, Amathus, Jericho, and Sepphoris. Thus, says Josephus, one might suppose with bitter irony, "they passed from a monarchy to an aristocracy."

Triumph of Pompey

Meanwhile the Roman citizens witnessed the spectacle of Pompey's triumph (his third and greatest) – the grandest Rome had ever seen. Huge placards came first, with enumeration of the thousand castles and nine hundred cities conquered, the eight hundred galleys taken from the pirates, the thirty-nine cities refounded. Then followed the splendid spoils, and among them the golden vine of Palestine; then the mass of prisoners who added a peculiar interest to the procession by appearing not as slaves in chains but each in his national costume. Immediately in front of the Conqueror himself, in jeweled vehicle, surrounded by pictures of his exploits, came the 362 captive Princes of the East, and among them the King of Judaea. Even at the time the countrymen of Pompey selected trophies of the strange city from the vast variety of objects and people of whom they had heard so much – and bestowed upon him as his especial title "our hero of Jerusalem."

It was the rare exception, the result of rare humanity of the conqueror, that on reaching the fatal turn in the Sacred Way, whence the triumphal procession ascended the Capitoline Hill, the prisoners were not led to execution, but either sent back to their homes or remained in Rome for whatever fortunes might await them.

Foundation of the Church of Rome

Among the train of inferior captives who were thus left after the triumph, and who, on recovering their liberty either did not have the means or inclination to return to their distant country, was the large band of Jewish exiles to whom was assigned a district on the right bank of the Tiber, convenient for the landing of merchandise to a people whose commercial tendencies were now developing. This singular settlement, receiving constant accessions from the East, became the wonder of the Imperial city, with its separate burial-places copied from the rock-hewn tombs of Palestine, with its ostentatious observance, even in the heart of the great metropolis, of the day of rest; with the basket and bundle of hay which marked the Jewish peasant wherever he was found; with its mysterious power of fascinating the proud Roman nobles by the glimpses which it gave of a better world. By establishing this community Pompey was, although he knew it not, founder of the Roman Church.

Remnants of the Asmoneans

Among the more illustrious hostages were Aristobulus, his uncle Absalom, and his children. It will be our endeavor to briefly follow the fates of these last remnants of the Maccabaean race, whose spirit still showed itself in their unquenchable patriotism and headlong resistance against overwhelming odds. Alexander, eldest of the sons of Aristobulus (who had married a daughter of Hyrcanus and thus might seem to represent both branches of the family) had escaped on the journey to Rome and in the family fortress of Alexandreum, for a time defended himself against Gabinius and the reckless chief, Antony, whose military capacity was first revealed on this excursion. It was taken and the mountain fastnesses which had been erected by the Asmonean Princes were all dismantled – "the haunts of the robbers", "the strongholds of the tyrants" as they are called by Roman writers.

57 B.C.

However, in a few months Aristobulus himself, with his son Antigonus, effected his flight from Rome and as if by instinct fled to those same castles, which, even in their ruined state, were as the nests of that hunted race. The conflict revived in the famous scenes of Central Palestine. The Roman army, which had entrenched itself in the world-old sanctuary of Gerizim, under the shelter of friendly Samaritans, broke out and finally overpowered the insurgents on the slopes of Tabor, the field of so many victories and defeats from Barak downwards to Napoleon.

49 B.C.

For a moment, by joining the cause of Caesar, under whose standard some of their countrymen fought at Pharsalia, there seemed a chance for the Jewish Princes to retrieve their fortunes. But amid their obscure entanglement in the struggle between the two mighty combatants for the empire of the world, Aristobulus (by poison) and Alexander (by decapitation) were removed from the scene. There now remained Antigonus, his sister Alexandra and the two children of Alexander, Aristobulus and Miriam (or Mary; better known by the more lengthened Grecian form of Mariamne). Round these princes and princesses revolves the tragedy in which the Asmonean dynasty finally disappeared. But in order to catch the thread of that intricate plot we must introduce the new character who appears on the scene.

Herod

Throughout the struggles which we have traversed, it is easy to discern the tortuous and ambitious policy of the crafty Idumaean Antipater, who had made himself indispensable both to the feeble Priest Hyrcanus and to the powerful chiefs of the Roman Republic. But Antipater himself now makes way for a name far more renowned in history, far more interesting in itself – his son Herod, whether by accident or design, surnamed the Great (According to the story of Christian writers, Herod's grandfather, himself Herod, was a slave in the temple of Ascalon, too poor to ransom his son Antipater when carried off by Idumaean robbers. The story receives some confirmation from Herod's attentions to Ascalon but is incompatible with the general account of the family given by Josephus). In the darker traditions of the Talmud, he was known only as the slave of King Jannaeus. The inferiority of his lineage was a constant byword of reproach among members of the Asmonean family, in whose eyes his sisters were fit for nothing but sempstresses, his brothers nothing but village schoolmasters. In the next generation, when his power on one side and his crimes on the other had drawn a halo or cloud round his head, the descent of Herod was alternately glorified or debased.

His Origin

In the annals of his secretary, Nicolas of Damascus, he was represented as a scion, not of the despised and hated Edomites, but of a noble Judaean family among the Babylonian exiles. Nor was this closer kinship altogether disclaimed by the Jews themselves. "Thou art our brother", they condescended to say to one of the sons of Herod, who wept over his alien origin. But it is not necessary to go beyond the historical facts. Whether by race or education, he belonged to that Edomite tribe, which, with singular tenacity, had retained the characteristics of its first father, Esau, through the long years which had elapsed since, in the patriarchal traditions, the two brothers had parted at the cave of Machpelah. In their wild nomadic customs, in their mountain warfare (clinging like eagles to their caverned fastnesses, unless when they descended for a foray on their more civilized neighbors) they were hardly distinguishable from a Bedouin tribe; yet, with that sense of injured kinship which breeds the deadliest animosities they maintained a defiant claim to hang on the outskirts and force themselves on the notice of the people of Israel; sheltering the revolted princes of Judah in their secluded glens; hounding the enemies of Jerusalem in the hour of her sorest need; claiming complete possession of the whole country for their own as if by the elder brother's right which the supplanter had stolen from them. If for a moment they had bowed beneath the sway of the first Hyrcanus, and consented to reunite themselves with the common stock of Abraham by the rite of circumcision, it was that they might once again have dominion and break their brother's yoke from off their necks.

His Rise (47 B.C.)

The first Antipater secured for himself the place of a vassal prince under Alexander Jannaeus; the second, as we have seen, became the master of the Phantom Priest Hyrcanus, and, alternately siding with each of the two parties which divided the Roman world, mounted to the high office of the Roman Procurator of Judaea, first through the favor of Pompey and then of Caesar. And now his son inherits the traditions of his house and nation, and the threats of that subtle influence by which Rome henceforth assumed control of Judaea. At 15, Herod was hardly more than a boy (the twice repeated remark of Josephus [Ant. xiv. 9, 2; B. 7. I., 4] that he was exceedingly young points to 15, not 25) when he was brought forward by his father into public life. Already, when he was a child going to school, his future greatness had been predicted by an ascetic seer from the Essenian settlement who called him "King of the Jews". The child thought that Menahem was in jest; but the prophet smacked the little boy on the back and charged him to remember these blows as signal that he had foretold to him his future destiny – what he might be and what, unfortunately, he became.

Like a true descendant of Esau, he was "a man of the field, a mighty hunter". He was renowned for his horsemanship. On one day of successful sport he was known to have killed no less than forty of the game of those parts – bears, stags, and wild asses. In the Arab exercises of the jerreedor throwing the lance in the archery of the ancient Edomites, he was the wonder of his generation. He had a splendid presence. He prided himself on His magnificently dressed black hair. When older and his hair turned gray, it was dyed to keep up an appearance of youth. Josephus points out that on one occasion when he sprang out of a bath where assassins had surprised him even his naked figure was so majestic that they fled before him. Nor was he destitute of noble qualities, however much obscured by the violence of the age and by the furious, almost frenzied, cruelty which despotic power breeds in Eastern potentates. There was a greatness of soul which might have raised him above the petty intriguers by whom he was surrounded. His family affections were deep and strong. In that time of general dissolution of domestic ties it is refreshing to witness the almost extravagant tenderness with which on the Plain of Sharon in the fervor of his filial love he founded the city of Antipatris; to the citadel above Jericho he gave the name of his Arabian mother Cypros; to one of the towers of Jerusalem, and to a fortress in the valley looking down to the Jordan (which still retains the name) he left the privilege of commemorating his beloved and devoted brother Phasael. In the lucid intervals of the darker days which beset the close of his career nothing can be more pathetic than his remorse for his domestic crimes, nothing more genuine than his tears of affection for his grandchildren.

His Cultivation

Nor were there wanting signs of a higher culture than any Judaean Prince had shown since the time of Solomon. He had an absolute passion for philosophy and history, and used to say that there could be nothing more useful or politic for a king than the investigation of the great events of the past. He engaged for his private secretary Nicolas of Damascus, one of the most accomplished scholars of the age, and author of a universal history in 144 books; and on his long voyages to and from Rome he loved to while away the hours by conversations on these subjects with Nicolas, whom for this purpose he took with him on board of the same ship.

One example of his own philosophic sentiment is preserved in the speech which Josephus ascribes to him, endeavoring to dispel the superstitious panic occasioned by an earthquake. Also appearing as we proceed is how completely he entered into the glories of Greek and Roman art – from the monuments which place him in the first rank of the masters of architecture in that great age of building. His contemporaries recognized in him one of those rare princely characters, who take a delight in beneficence and in its largest possible scope. Not only in Palestine itself, but in all the cities of Asia and Greece, which needed generous assistance, he freely gave it. At Antioch he left his mark in the polished marble pavement of the public square, and in the cloister which surrounded it. In many of the cities of Syria and Asia Minor he founded places for athletic exercises, aqueducts, baths, fountains, and (in the modern fashion of philanthropy) annexed to them parks and gardens for public recreation. With a toleration which seems beyond his time, but which kindles an admiration even in the Jewish historian, he repaired the Temple of Apollo at Rhodes, and settled a permanent endowment on the games of Olympia, the chief surviving relic of Grecian grandeur which he had visited on his way to Rome.

This was the man who now stepped into the foremost place of Jewish history. It might have seemed as if the cry of Esau were to be repeated: "Hast thou but one blessing? Bless me, even me also, O my father".

A chief of such largeness of mind, such generosity of disposition, such power of command, was well suited to take the lead in this distracted nation. Viewed as we now view him, through the blood-stained atmosphere of his later life, even the dubious eulogies of Josephus are difficult to understand. But viewed in the light of the nobleness of his early youth, and through the magnificence of his public works, it was natural that the judgment of his contemporaries should have differed from that of posterity, that he should have been invested with something of a sacred character, as a dreamer of prophetic dreams, a special favorite of Divine Providence, and that a large party in the community should have borne his name as their most cherished badge, regarding him as the nearest likeness which that age afforded to the Anointed Prince or Priest of the house of David, who had been expected by the earlier Prophets.

His Exploits in Galilee

The first scene on which Herod appears is full of instruction. Boy as he was, his father had appointed him to take charge of Galilee; which, partly from its border character whence it derived its name, partly from the physical peculiarities of its deeply-sunken lake, wild glens, and cavernous hills, had become the refuge of high-spirited insurgents, who in semi-civilized countries insensibly acquire both the reputation and character of bandits – the Highlands, the Asturias, the Abruzzi of Palestine. The young "Lord of the Marches", fired with the same spirit, whether politic or philanthropic, which had conferred such glory on Pompey and Augustus in their repression of the pirates of the Mediterranean and the brigands of Italy, determined to crush those lawless robbers of his own country.

In Syria his fame rose to the highest pitch. In villages on the Lebanon his name was the burden of popular ballads, as their Heaven-sent deliverer from the incursions of the Galilean highlanders. But in Judaea these acts of summary justice wore another aspect. The chief of the robber band, Hezekiah, was, in the eyes of the residents at Jerusalem, probably the patriot (perhaps in reality), the Tell of his time, as he certainly was the father of a gallant family of sons who were to play a like part hereafter.

His Trial (47 B.C.)

Jerusalem was filled with the echoes of these Galilean exploits. On one hand the messengers of Herod's victories vied with each other in their reports, and in awakening the public apprehension of his possible designs on the monarchy. On the other hand, the mothers of the victims of his zeal hurried to the capital and every time the Priest-King Hyrcanus appeared in the Temple Court they beset him with entreaties not to allow the murder of their children to go untried and unconvicted or to pass unchallenged. Reluctantly, the feeble Prince summoned the son of his patron to appear before the Sanhedrin Council, which now for the first time appears in Jewish history. It sat, probably now as afterwards, in the Hall of Gazith or Squares, so called from the hewn, square stones of its pavement. The royal Pontiff was present along with the chief teachers of the period. The legendary account of the scene, although disguised under wrong names and dates, is one of the very few notices which the Talmudic (according to Derenbourg, the king in this story is made Jannaeus, and the fearless judge Simon the son of Shetach) traditions take of the eventful course of Herod's life. "The slave of the King of Judah", said the Rabbinical tale, "had committed a murder." The Sanhedrin summoned the King to answer for the crimes of his slave. "If the ox gore any one" (Ex. 21:28), said the interpreters of the law to the King, "the owner of the ox shall be responsible for the ox." The King seated himself before them. "Rise", said the Judge. "Thou standest not before us, but before Him who commanded and the world was created" (Deut. 19:17). The King appealed from the Judge to his colleagues. The Judge turned to the right hand and to the left, and his colleagues were silent. Then said the Judge: "You are sunk in your own thoughts. God who knows your thoughts will punish you for your timidity". The Angel Gabriel smote them and they died.

It is instructive to turn to the actual scene of which this is the distorted version. It was indeed a splendid apparition, but not of the Angel Gabriel that struck the wise Councilors dumb. When Herod was summoned before them for the murder of the Galileans, instead of a solitary suppliant, clothed in black, with his hair combed down, and his manner submissive, such as they expected to see, there came a superb youth in royal purple, his curls dressed out in the height of aristocratic fashion, surrounded by a guard of soldiers and holding in his hand the commendatory letters of Sextus Caesar, the Governor of Syria, cousin of the great Julius. The two chiefs of the Sanhedrin at that juncture were Abtalion and Shemaiah. It was probably Abtalion who counselled silence. His maxim had always been: "Be circumspect in your words". But Shemaiah rose in his place and warned them that to overlook such a defiance of the law would be to ensure their own ruin. For a moment they wavered. But, warned by Hyrcanus, Herod escaped and years later lived to prove the truth of Shemaiah's warning, sweeping away the vacillating Council, though at the same time rewarding the prudence of Abtalion, if not the courage of Shemaiah.

The story illustrates the waning of the independence of the nation before the rise of the new dynasty, backed as it was by all the power of Rome. It was to Herod that the sceptre was destined to pass.

Death of Antipater (43 B.C.)

Antipater, his father, long held Hyrcanus in his grasp. But at last he fell victim to the struggles of his puppet to escape from him and the two brothers, Phasael and Herod, were left to maintain their own cause. At once Herod endeavored to spring into his father's place by a stroke, which, but for the jealousies of his own household would have probably been crowned with complete success.

Contest with Antigonus (42 B.C.)

In his early years he had married an Idumaean wife, Doris, by whom he had a son named after his father Antipater – a child now, but destined to grow up into the evil genius of his house. He now determined on a higher alliance. The beautiful and high-spirited Mariamne united in herself the claims of both the rival Asmonean princes. She was the grand-daughter of both Hyrcanus and Aristobulus.

From this time Hyrcanus became the fast friend of Herod, crowned with garlands whenever he appeared, pleading his cause before the Roman Triumvir. However, Aristobulus had left behind not only Mariamne, but a passionate and ambitious son, Antigonus, who could not see the kingdom pass away without a struggle, even to his niece's husband. There was only one foreign ally whom he could invoke against the great Republic of the West. It was the rising kingdom of the East – the Parthian monarchy, which offered to play the same part for Judaea against Rome that Egypt had formerly played against Assyria.

Crassus (54 B.C.)

A natural brotherhood of misfortune and joy seemed to have arisen from the fresh recollection of the campaign of Crassus. Jerusalem still suffered under the loss of its accumulated treasures, which, in spite of the most solemn adjurations, the rapacious Roman had carried off from its Temple. Parthia still rejoiced in the triumph which its armies had won over his scattered host on the plains of Haran, the ancient cradle of the Jewish race.

The Parthians (40 B.C.)

By force and by fraud, Hyrcanus and Phasael were induced to give themselves into the hands of the Parthian general, and were hurried away into the Far East. Phasael died, partly by his own desperate act when he saw that he was doomed, partly by the treachery of Antigonus, but not without a glow of delight on hearing that his beloved brother had escaped. The fate of Hyrcanus was singularly instructive. To take the life of so insignificant a creature was not within the range of Antigonus' ambition. All that remained was to debar him from the Priesthood. For this the slightest bodily defect or malformation was a sufficient disqualification. The nephew sprang upon the uncle, and with his own teeth gnawed off the ears of the harmless Pontiff, leaving him in that mutilated condition in the Parthian court. This strange physical deposition from a spiritual office in part succeeded, in part failed of its purpose.

In those remote regions, the prestige of one who had once been chief of the Jewish nation was not easily broken. After receiving every courtesy from the Parthian king, Hyrcanus, was allowed to move to the vast colony of his countrymen who still inhabited Babylon. By them he was hailed as High Priest and King and loaded with honors, which he gratefully accepted. What his fate was to be in Jerusalem we shall presently see.

Escape from Antigonus (40 B.C.)

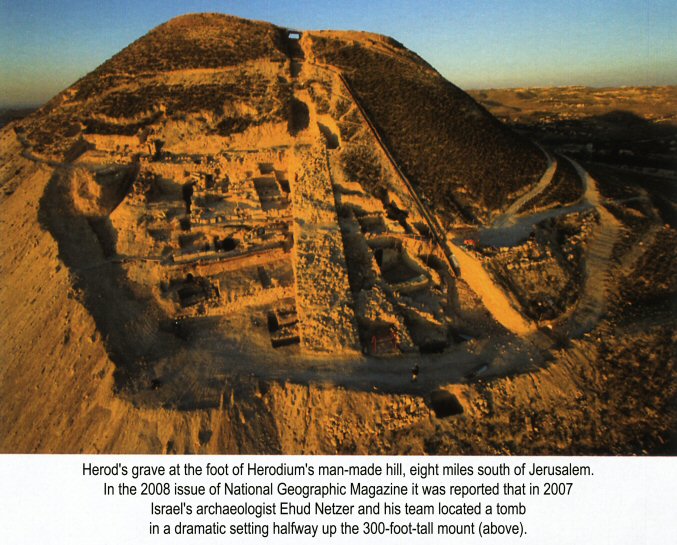

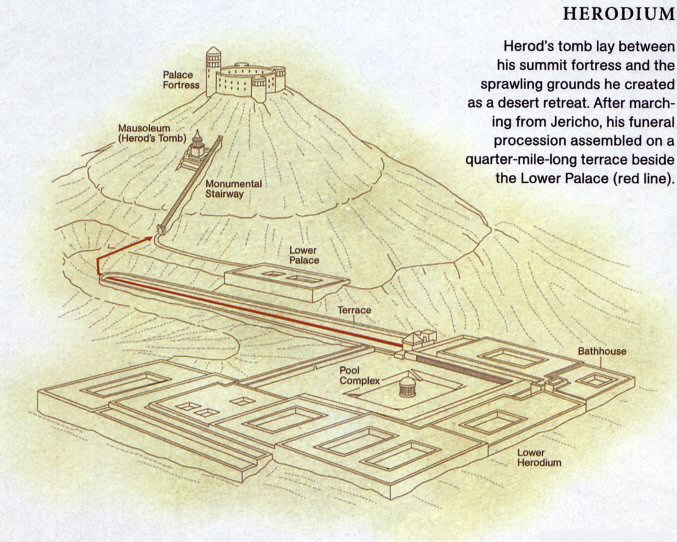

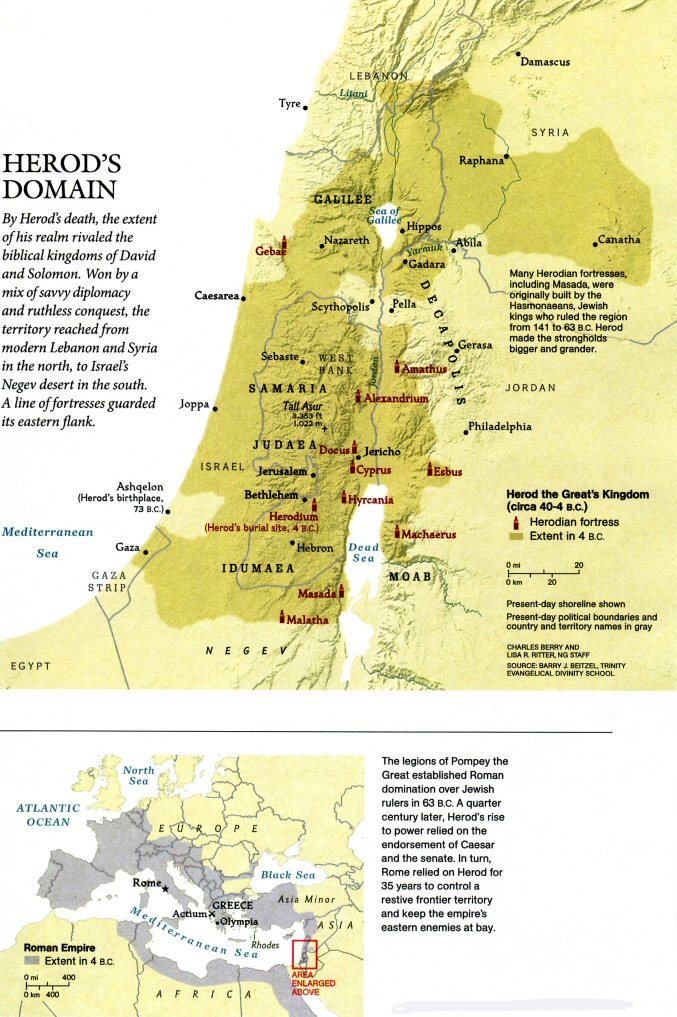

Meanwhile, the plot in Palestine had deeply thickened. On the day that Hyrcanus and Phasael had been carried off to Parthia, Herod escaped, with all the members of his family he could collect, and hurried into his native hills in the south of Judaea. "It would have moved the hardest of hearts", says the historian Josephus, "to have seen that flight" – his aged mother, youngest brother, clever sister, betrothed bride, with her still more sagacious mother and the small children of his earlier marriage. Never was that high spirit so nearly broken. It was a march which he never forgot. Years later he built for himself and his dynasty a fortress and burial-place bearing his name, and corresponding to those of which the Asmonean princes had set the example (the Herodium) on the square summit of the commanding height at the foot of which he had successfully secured safety over his pursuers. From thence he took refuge in the almost inaccessible stronghold of the ancient kings of Judah, afterwards destined to be the last stronghold of the expiring people – Masada, by the Dead Sea. But even Masada, even Petra to which he next fled, was not secure. Regardless of the blandishments of Cleopatra at Alexandria, regardless of the storms in the Mediterranean, he halted not till he reached Rome and laid his grievances before Antony, his first patron.

He obtains the Kingdom

It was the fatal turning-point of his life. The prize of the Jewish monarchy was now unquestionably and for the first time offered to him by Antony and Octavianus Caesar. He entered the Senate as the rightful advocate of the young Prince Aristobulus. He left it, walking between the two Triumvirs, as "King of the Jews".

Capture of Jerusalem (37 B.C.)

It was still after many vicissitudes and hair-breadth escapes that, with the assistance of the Roman troops commanded by Sosius, he stormed Jerusalem. It was the twenty-fifth anniversary of the day on which Pompey had entered the Temple, and it only partially escaped the horrors of the same desperate resistance and the same ruthless massacre which has been the peculiar fate of almost every capture of Jerusalem, from Nebuchadnezzar down to Godfrey. But the noblest parts of Herod's finer nature were called forth. He exclaimed: "The dominion of the whole civilised world would not compensate to me for the destruction of my subjects"; and he actually bought off the rapacious Roman soldiers out of his own personal munificence.

These brighter traits were now rapidly merged in the darkening shadows of his later career. With a vindictiveness which he had learned only too well in the school of his friends the Roman triumvirs, Herod pursued to death the followers of Antigonus, including, according to Jewish tradition, the whole teaching body of the nation. Of the whole of that Council which had sat in judgment on his youthful excesses in Galilee, only three are said to have escaped – the prudent Abtalion, the courageous Shemaiah, and the son of Babas, not, however, without loss of his eyesight. Even the coffins of the dead were searched to see that no living enemy might escape the vigilant persecutor. The proud spirit of Antigonus gave way under this overwhelming disaster. He came down from his lofty tower and fell at the feet of Sosius in an agony of tears. The hard-hearted Roman, not touched by the disastrous misery of the gallant Prince, burst into roars of brutal laughter, in ridicule called him by the name of the Grecian maiden Antigone, and hurried him off in chains to Antony at Antioch. Antigonus was in the hands of those who knew neither justice nor mercy. A bribe from Herod to Antony extinguished the last spark of compassion. So strong was the attachment of the Jewish nation to the Maccabaean race, as well as any bearing the royal name, felt that regardless of the scruple which had hitherto withheld even the fiercest of Roman generals from thus trampling on a fallen king, the unfortunate Antigonus was lashed to a stake like a convicted criminal, scourged by the rods of the relentless lictors and ruthlessly beheaded by the axe of their fasces. With a Mattathias the Asmonean dynasty began, with a Mattathias it ended. Coins still exist bearing the Hebrew name for his office of High Priest and the Greek name of his royal dignity; while on medals struck by Sosius at Zacynthus to commemorate his victory for the first time appears the well-known melancholy figure of Judaea captive (in the British Museum), with her head resting on her hands, and besides her crouches the form of her last native king, stripped and bound in preparation for his miserable end.

Priesthood of Hananel (36 B.C.)

Yet the Maccabaean family was not extinct. There still remained Hyrcanus, the original friend of Herod and Herod's father, as well as Aristobulus and Mariamne, the two grandchildren of Aristobulus the king. We will trace each of these to their end. Whether from policy or old affection, Herod, now seated on the throne of Judaea, invited Hyrcanus from his honorable retreat in Babylonia to the troubled scene at Jerusalem. Hyrcanus was to share the regal dignity with him, to take precedence of him, was called his father, enjoyed every outward privilege which was his before, except only the High Priesthood from which he was excluded by the extreme punctiliousness that amid all the scandalous vices of the time still shrank from nominating a pontiff with the almost imperceptible blemish inflicted by the teeth of Antigonus. For this high office, Herod summoned Hananel, from Babylon – a Jewish exile, an ancient friend of unquestionably priestly descent. But this at once provoked a new feud.

Priesthood of Aristobulus III (35 B.C.)

However much the royal dignity might be lost to the Asmonean house, yet there was no reason why the Priesthood, for which Hyrcanus was thus incapacitated, should not be continued in their line and for this purpose there was at hand Aristobulus, the maternal grandson of Hyrcanus and brother of Mariamne, whom shortly before his final success Herod had married at Samaria, the city which the Romans had founded anew and which was henceforth one of Herod's chief resorts. It was as if the majestic beauty which had distinguished the Maccabaean family from Judas downwards reached its climax in this brother and sister. And their mother Alexandra exhibited the courage and craft which had been so conspicuous in Jonathan and the first Hyrcanus. She was "the wisest woman" in his whole court, so Herod thought. She was the one to whose opinion he most deferred. Both she and her daughter were indignant that in coming years the charming boy (now the sole representative of their house) should be kept out of the Priesthood by a stranger. By the same authority that Solomon and the Syrian kings had exercised before him, partly by remonstrance's and partly by intrigues they succeeded in inducing Herod to supersede Hananel and appoint Aristobulus in his place. His mother's heart misgave her, and with her friend Cleopatra, in some respects a kindred spirit, she had planned a flight into Egypt for herself and him. But the plan was discovered and the fate which she had feared for her son was precipitated by the very object which she had striven to obtain for him. As so often on other occasions in Jewish history, it was amid the peculiar festivities and solemnities of the Feast of Tabernacles that he was to assume his office. He was just seventeen; his commanding stature beyond his age, his transcendent beauty, his noble bearing, set off by the High Priest's gorgeous attire, at once riveted the attention of the vast assembly, and when he ascended the steps of the altar for the sacrifice it recalled so vividly the image of his grandfather, Aristobulus, so passionately loved and so bitterly lamented, that, as in the well-known scene in a great modern romance the recognition flew from mouth to mouth; the old popular enthusiasm was revived, which, it became evident would be satisfied with nothing short of restoring to him the lost crown of his family.

Murder of Aristobulus

The suspicions of Herod were excited. The joyous Feast was over and the youthful High Priest, fresh from his brilliant display, was invited to his mother's palace among the groves of Jericho – the fashionable watering-place of Palestine. Herod received the boy with his usual sportiveness and gaiety. It was one of the warm autumnal days of Syria, and the heat was even more overpowering in that tropical valley. In the sultry noon the High Priest and his young companions stood cooling themselves beside the large tanks which surrounded the open court of the Palace and watching the gambols and exercises of the guests or slaves, as, one after another, they plunged into these crystal swimming-baths. Among these was the band of Gaulish guards, whom Augustus had transferred from Cleopatra to Herod and whom Herod employed as his most unscrupulous instruments. Lured on by these perfidious playmates the princely boy joined in the sport and then, as at sunset the sudden darkness fell over the happy scene, the wild band dipped and dived with him under the deep water; and in that fatal baptism life was extinguished. When the body was laid out in the Palace the passionate lamentations of the Princesses knew no bounds.

The news flew through the town and every house felt as if it had lost a child. The mother suspected but dared not reveal her suspicions and in the agony of self-imposed restraint and in the compression of her determined will, trembled on the brink of self-destruction. Even Herod, when he looked at the dead face and form retaining all the bloom of youthful beauty, was moved to tears – so genuine, that they almost served as a veil for his complicity in the murder. And it was not more than was expected from the effusion of his natural grief that the funeral was ordered on so costly and splendid a scale as to give consolation even to the bereaved mother and sister.

However, that mother still plotted and now with increased restlessness against the author of her misery. That sister still felt secure in the passionate affection of her husband, on whose nobler qualities she relied when others doubted. But now the tragedy spread and deepened and intertwined itself as it grew with the great struggle waging on the larger theatre of history.

On one side of Herod's court ranged the two Princesses of the Asmonean family, on the other Cypros and Salome, the mother and sister of Herod himself who resented the contempt with which the royal ladies of the Maccabaean house looked down on the upstart Idumaean family. Ambitious of annexing Palestine, Cleopatra in Egypt was now endeavoring to inveigle Herod himself by her arts – poisoning the mind of Antony against him. In Rome were Antony and Augustus Caesar contending for the mastery of the world, and Herod alternately pleading his cause before the one and then the other – before his ancient friend Antony and then, after the battle of Actium, before the new ruler who had the magnanimity to be touched by the frankness with which Herod urged his fidelity to Antony as the plea for the confidence of Augustus.

Death of Hyrcanus (30 B.C.)

Meanwhile, like a hunted animal turned to bay, his own passions grew fiercer, his own methods more desperate. Aristobulus, the young, the beautiful, had perished. But there remained the aged Pontiff Hyrcanus. Insignificant, humiliated, and mutilated as he was, there was still the chance that the same veneration which had encircled him in Chaldaea might gather round him in Palestine and that even the Roman policy might convert him into a rival King. In a fatal moment, listening to the counsels of his restless daughter Hyrcanus gave to Herod the pretext needed for an accusation and (so carefully were preserved the forms of the Jewish State) a trial and a judgment; and at the age of eighty the long and troubled life of the Asmonean Pontiff was cut off.

The intestine quarrels in the Herodian court now became so violent that the Princesses of the rival factions could not be allowed to meet. The mother and sister of Herod were lodged in the fastness which was more peculiarly his own – Masada, by the Dead Sea. His wife and her mother remained in the castle dear to them as the ancient residence and burial place of their family – Alexandreum.

Murder of Mariamne (29 B.C.)

At this crisis of her history there is something magnificent in the attitude of Mariamne – she never lowered herself to the base intrigues of those surrounding her and never disguised from Herod her sense of the wrongs he had inflicted on her house. When he returned from his interview with Augustus, inspired by the passionate affection of his first love to announce his success in winning the favor of the conqueror of Actium, she turned away and reproached him with the murders of her brother and grandfather.

Now was the moment when Salome saw her opportunity. She played on every chord of the King's suspicious temper, till it was irritated past endurance. Mariamne was arrested, tried, and condemned. Even in these last moments, she rose superior to all around her. Unlike her mother, she had never shared in plots and counterplots to advance the interests or secure the safety of the Asmonean house. If she spoke in behalf of her kindred, it was boldly and frankly to a husband on whose affections and generosity, if left to himself, she knew she could rely. Unlike that ambitious princess, now her extreme adversity, she maintained a serenity in which her mother failed. It is the characteristic difference of the two natures that the restless woman who had employed every miserable art in order to protect her family, now that the noblest of her race for whom she had hazarded all was on the point of destruction, lost all courage and endeavored to clear herself by cowardly reproaches of her daughter in justification of the King. However, Mariamne answered not a word. "She smiled a dutiful though scornful smile" (Tragedy of Mariam, the Fair Queen of Jewry, act v. scene I). For a moment, her look showed how deeply she felt for the shame of a mother; but she went on to her execution with unmoved countenance, with unchanged color – she died as she had lived, a true Maccabee. Perhaps the most affecting and convincing testimony to her great character was Herod's passionate remorse. In a frenzy of grief he invoked her name, he burst into wild lamentations, and then, as if to distract himself from his own thoughts, he plunged into society; he had recourse to all his favorite pursuits; he gathered intellectual society round him; he drank freely with his friends; he went to the chase. And then, again, he gave orders that his servants should keep up the illusion of addressing her as though she could still hear them; he shut himself up in Samaria, the scene of their first wedded life, and there, for a long time, attacked by a devouring fever, hovered on the verge of life and death. Of the three stately towers which he afterwards added to the walls of Jerusalem, one was named after his friend Hippias, the second after his favorite brother, Phasael, but the third, most costly and most richly worked of all, was the monument of his beloved Mariamne.

Death of Alexandra (28 B.C.)

It is not necessary to pursue in detail the various entanglements by which the successive members of the Herodian family fell victims to the sanguinary passion which now took possession of the soul of Herod, except for this one example: according to Rabbinical traditions, compressing into one scene this series of crimes and sorrows, one young maiden whom he proposed to marry escaped and sprang from a housetop killing herself. He embalmed her body keeping it for seven years. Alexandra was the first to fall.

End of the sons of Mariamne (16-6 B.C.)

There remained the two sons of Mariamne, Alexander and Aristobulus, in whom their father delighted to see an image of their lost and lamented mother. He sent them to be educated at Rome in the household of Pollio, the friend of Virgil; and when they returned to Palestine, with all the graces of a Roman education and with the royal bearing, apparently inextinguishable in the Asmonean house, it seemed, from the popular enthusiasm which they excited, that they might yet carry on that great name; and their father, by the high marriages which he prepared for them, i.e., for Alexander the daughter of the King of Cappadocia, for Aristobulus his cousin, the daughter of Salome, he hoped to have consolidated their fortunes and reconciled the feuds of the two rival families.

But all was in vain. With their mother's beauty, they inherited her haughty and disdainful spirit. They cherished her in an undying memory. Her name was always on their lips and in their lamentations for her were mingled curses on her destroyer; when they saw her royal dresses bestowed on the ignoble wives of their father's second marriage, to his face they threatened him that they would soon make those fine ladies wear hair-cloth instead; and to their companions they ridiculed the vanity with which in his declining years he insisted on the recognition of his youthful splendor, his skill as a sportsman, and even his superior stature. And now there was a new element of mischief – his eldest son Antipater, who watched every opportunity of destroying his father's interest in these aspiring youths – the very demon of the Herodian house.

6 B.C.

He and the she-wolf Salome at last accomplished their object and the two young Princes were tortured, tried, and executed at Sebaste, the scene of their mother's marriage, and interred in the ancestral burial-place of the Alexandreum. If not in lineage yet in character they were the last of their race. Their children, in whose behalf the better feelings of Herod broke out when, with tears and passionate kisses of affection which no one doubted to be sincere, he endeavored to make plans for their prosperous settlement, were gradually absorbed into the Herodian family; and although two of them, Herod Agrippa and Herodias, played a conspicuous part in the sacred history which follows, they lost the associations of the Maccabaean name and never kindled the popular enthusiasm in their behalf.

In the fall of the Asmonean dynasty, the death of Mariamne and her sons represents the close of the last brilliant page of Jewish history. The visions of a Son of David retired into the background as long as there was a chance of a Prince from that august and beautiful race. It was only when the last descendant of those royal Pontiffs passed away that wider visions again filled the public mind and prepared the way for One who, whatever might be His outward descent, in His spiritual character represented the best aspect of the Son of Jesse. And even then the famous apostolic names of the coming history were inherited from the enduring interest in the Maccabaean family – John, Judas, Simon, and Matthias or Mattathias. Above all, the name Mary, so sweet to Christian ears, no doubt owes its constant repetition in the narratives both of Evangelists and Josephus, not to Miriam the sister of Moses, but to her later namesake, the high-souled and lamented princess Mariamne.

Death of Herod (4 B.C.)

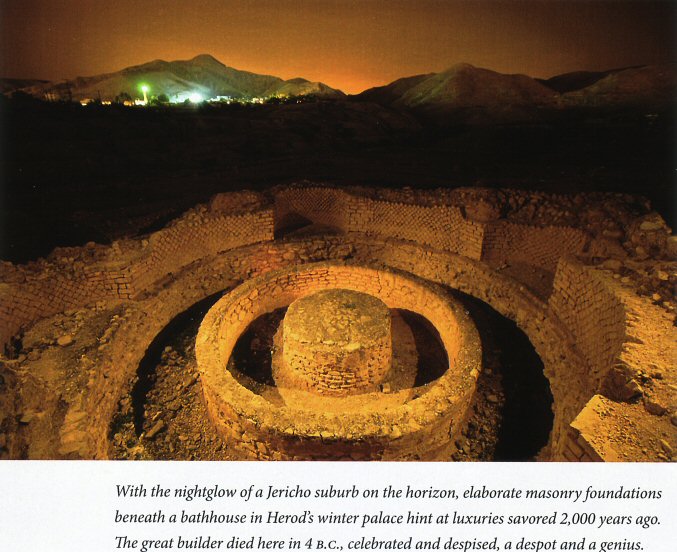

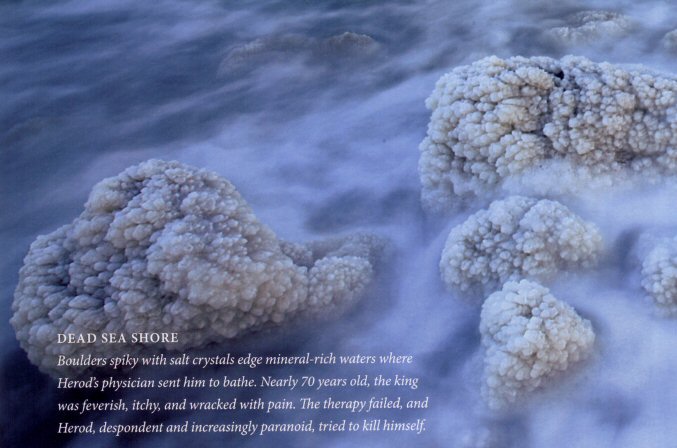

And now came the end of Herod himself. The palace was haunted by memories of the Asmonean Queen. "The ghosts of the two murdered Princes," writes the historian Josephus, rising from his prosaic style almost to the tone of the Aeschylean Trilogy, "wandered through every chamber of the palace, and became the inquisitors and informers to drag out the hidden horrors of the Court." Antipater, villain of the family, had at last paid the forfeit of his tissue of crimes. But his father was already in his last agonies in the Palace of Jericho – the scene of such splendid luxury and such fearful crime. As a remedy for the loathsome disorder of which he was the prey, he was carried across the Jordan to one of the loveliest spots in Palestine, the hot sulphur springs which burst from the base of the basaltic columns in the deep ravine on the eastern shore of the Dead Sea; according to popular belief issuing from the bottomless pit. There, in the Beautiful Stream as the Greeks called it, the unhappy King tried to burn and wash away his foul distempers. But it was all in vain. Because as he lay tossing in those sulphurous baths his eyes could view, rising above the western hills, the fortress called by his name which was fixed for his burial. And there he must go. Back to Jericho the dying King was borne. The hideous command which in his last ravings he gave to cause a universal mourning through the country by the slaughter of the chief men of the State, whom he had imprisoned for that purpose in the hippodrome of Jericho, was happily disobeyed. His sister Salome, who had so much on her conscience, spared herself this latest guilt; and when the body of Herod was carried to its last resting-place, it was attended with unusual pomp, but not with unusual crime. For seven long days the procession ascended the precipitous passes from Jericho to the mountains of Judaea. With crown and sceptre and under a purple pall the corpse of the dead King lay. Round it were the numerous sons of that divided household; then followed his guards and the three trusty bands of Thracian, German and Celtic soldiers who, as it were, had long been the Janissaries of his court; then through those arid hills defiled the army, and then five hundred slaves with spices for the burial. According to the fashion of those days, when each dynasty or branch of a dynasty had its sepulchral vault in its own special fortress, the remains of the dead king were carried up to that huge square shaped hill which commands the pass to Hebron, on the summit of which Herod, in memory of his escape on that spot thirty-six years before, had built a vast palace and called it by his name, Herodium (the conspicuous hill near Bethlehem called the 'Frank Mountain' or Jebel Fureidis, was first identified with the Herodium by Robinson. It is described at length by Josephus).

Such, disengaged from its labyrinthine intricacy, is the story of the last potentate of commanding force and world-wide renown that reigned over Judaea. It is a character which, had it been in the Biblical records, would have ranked in thrilling and instructive interest beside that of the ancient Kings of Israel or Judah. The momentary glimpses of him which we gain in the New Testament, through the story of his conversation with the Magi and his slaughter of the children of Bethlehem, are quite in keeping with the jealous, irritable, unscrupulous temper of the last "days of Herod the King" (Matt. 2:1), as we read them in the pages of Josephus.

His Character

But this is only a small portion of his complex career. The plots bred in the atmosphere of polygamy, the foul and midnight murders, the thirst for cruelty growing with its gratification, are features of Oriental and despotic life only too familiar to us in the history even of David. There is something in the penitence of Herod which reminds us of Uriah's murderer, though in Psalm or prayer it has never been enshrined for the admiration of posterity. Besides the intrinsic interest of the story is the pathos which it possesses as the central element in the drama which closed the Asmonean history. He is the Jewish Othello, but with more than a Desdemona for his victim. In his closing speech, when the Moor of Venice casts about for someone to whom he may compare himself, it was long thought by the commentators that there was none so suitable as Herod, "the base Judaean, who threw a pearl away richer than all his tribe" (Othello). Whether this was so or not, a dramatic piece on the subject had already been constructed by a gifted English lady, with a knowledge of the Herodian age surprising for the seventeenth century (Elizabeth Carew). When Voltaire apologized to the French public for having chosen Mariamne for the subject of one of his poetical plays, he rose to its grandeur with an enthusiasm unlike himself. "A king to whom has been given the name of Great, enamored of the loveliest woman in the world; the fierce passion of this king so famous for his virtues and for his crimes – his ever-recurring and rapid transition from love to hatred, and from hatred to love – the ambition of his sister – the intrigues of his concubines – the cruel situation of a princess whose virtue and beauty are still world-renowned, who had seen her kinsmen slain by her husband, and who, as the climax of grief, found herself loved by their murderer – what a field for imagination is this! What a career for some other genius than mine!" (Salvador). And when at last another genius arose (Byron), who had, as Goethe observed, a special aptitude for apprehending the ancient Biblical characters, there are few of his poems more pathetic in themselves and more true to history than that which represents the unhappy king, wandering through the galleries of his palace and still invoking his murdered wife –

Oh, Mariamne! now for thee

The heart for which thou bled'st is bleeding;

Revenge is lost in agony,

Oh Mariamne! where art thou

Thou canst not hear my bitter pleading:

Ah ! couldst thou – thou wouldst pardon now,

Though Heaven were to my prayer unheeding.

She's gone, who shared my diadem;

She sank, with her my joys entombing;

I swept that flower from Judah's stem,

Whose leaves for me alone were blooming;

And mine's the guilt, and mine the hell,

This bosom's desolation dooming;

And I have earned those tortures well,

Which unconsumed are still consuming!

But the importance of Herod's life does not end with his personal history. He created in great part that Palestine which he left behind as the platform on which the closing scenes of the Jewish, the opening scenes of the Christian Church were to be enacted.

His Public Works in Palestine

Few men have ever lived who, within such short a time, so transformed the outward face of a country. That Grecian, Roman, Western coloring which Antiochus had vainly tried to throw over the gray hill and rough towns of Judaea was fully wrought out by Herod the Great. It would seem as if, to manifest gratitude for his gracious reception by Augustus Caesar and for the Emperor's visit to Palestine, he was determined to plant monuments of him throughout his dominions.

Caesarea Philippi

At the extreme north, on the craggy hill which overhangs the rushing source of Jordan, rose a white marble temple dedicated to his patron, which for many years superseded both the Israelite name of Dan and the Grecian name of Paneas by Caesarea.

Sebaste (25 B.C.)

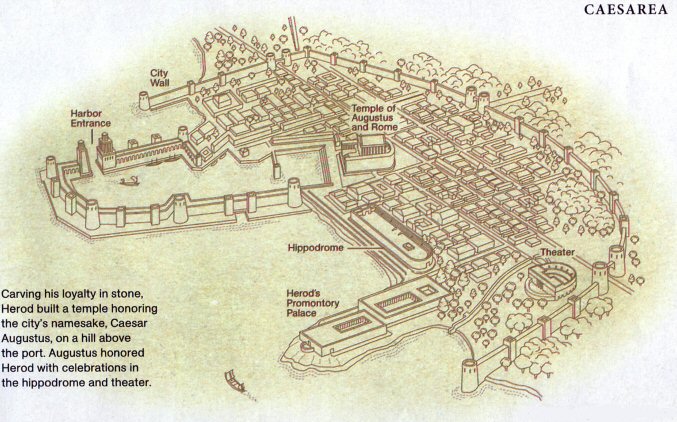

In the center of Palestine, on the beautiful hill of the ancient Samaria, laid waste by Hyrcanus I, the scene of his marriage with Mariamne, he built a noble city of which the colonnades still in part remain, to which he gave the name Sebaste – the Greek version of Augusta. On the coast,beside a desert spot hitherto only marked by the Tower of Strato, with a village at its foot, he constructed a vast haven which was to rival the Piraeus. Around and within it were splendid breakwaters and piers.

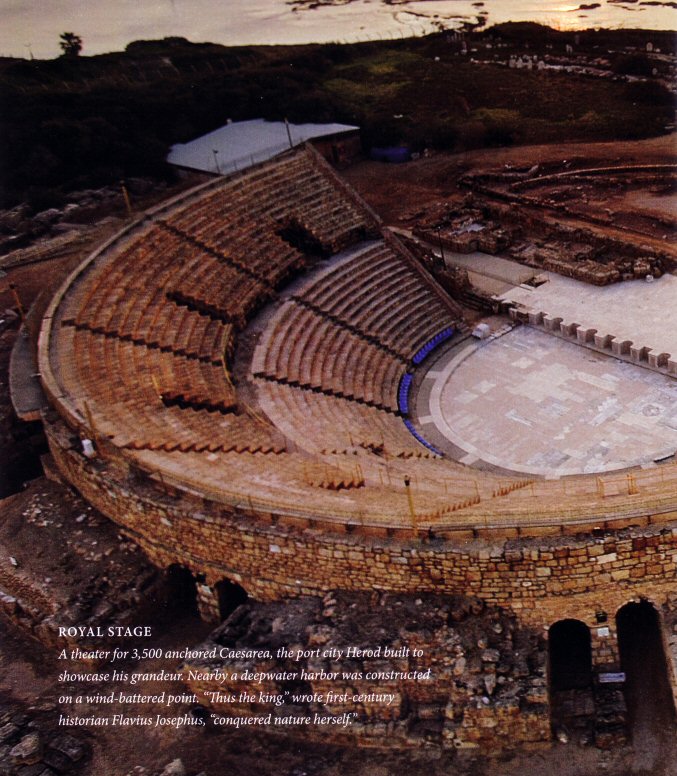

Caesarea Stratonis (10 B.C.)

Abutting on it was erected a city so magnificent with an array of public and private edifices that it ultimately became the capital of Palestine, throwing Jerusalem itself into a place altogether secondary. Houses of shining marble stood round the harbor; on a rising ground in the center, as in a modern crescent, rose the Temple of Augustus which again gave the name of Caesarea to the town – out of which looked on the Mediterranean two colossal statues; one of Augustus, equal in proportions to that of the Olympian Jupiter, one of the city of Rome, equal to that of the Argive Juno. Further down the coast he rebuilt the ruined Grecian city of Anthedon, and in commemoration of the visit of his friend the able minister of Augustus, gave it the name of Agrippeum;and, as over the portico of the Pantheon at Rome, over the gate of this Syrian city was deeply graven the name of Agrippa. In all these maritime towns, as far north as the Syrian Tripolis, and, not least, in that Hellenised city of Ascalon, to which Christian tradition assigned the origin of his ancestors, he established the luxurious and wholesome institutions of baths, fountains, colonnades, and in the inland cities – romantic Jericho, and holy Jerusalem – added the more questionable entertainments of Greek theatres, hippodromes, and gymnasia, which in the time of the Maccabees had caused much scandal; and the splendid, but to the humane and reverential spirit of the Jewish nation still more distasteful spectacles of the Roman amphitheatre.

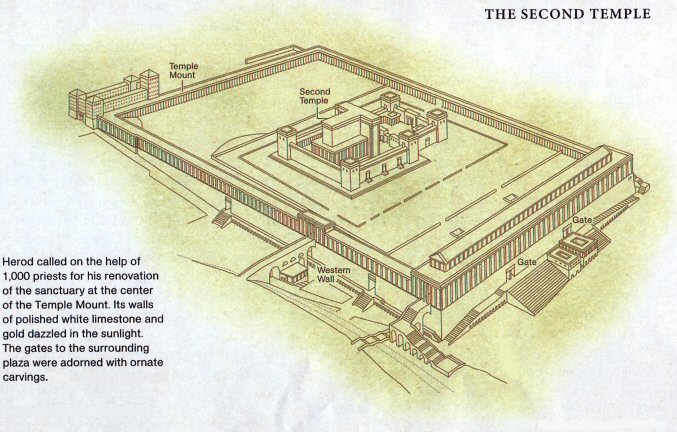

The Temple of Jerusalem (17 B.C.)

But the great monument of himself which he left was the restored, or, more exactly, the rebuilt Temple at Jerusalem. A Jewish tradition connected this prodigious feat with the miserable crimes of his later years. It was said that he consulted a famous Rabbi, Babas the son of Bouta – the only one who, as it was believed, had survived the massacre of the Teachers of the Law and who himself had his eyes put out – how he should appease the remorse which he now felt, and that the Rabbi answered: "As thou hast extinguished the light of the world, the interpreters of the law, work for the light of the world by restoring the splendor of the Temple." If this be so, the Temple, in its greatest magnificence was, like many a modern Cathedral, a monument of penitence. Indeed, it might have been urged that this elaborate restoration was only the fulfilment of the idea of an enlarged Temple on a grander scale, which, from the visions of Ezekiel down to those of the Book of Enoch, had floated before the mind of Jewish seers. But, the sacredness of the building and the mistrust of Herod created difficulties which required all his vigor and craft to overcome.

The Rebuilding

So serious had they seemed that his prudent patron at Rome was supposed to have dissuaded the undertaking altogether. "If the old building is not destroyed", said Augustus, "do not destroy it; if it is destroyed, do not rebuild it; if you both destroy and rebuild it, you are a foolish servant." The scruple against demolishing even a synagogue before a new one was built was urged with double force now that the Temple itself was menaced. It was met by the casuistry of the same wise old counsellor who had suggested the restoration to Herod. "I see", said Babas, "a breach in the old building which makes its repairs necessary." Not for the last time in ecclesiastical history has a small rift in an ancient institution been made the laudable pretext for its entire reparation. Herod himself fully appreciated the delicacy of the task. By a transparent fiction, the existing Temple was supposed to be continued into the new building. The worship was never interrupted; and, although actually the Temple of Herod, it was still regarded as identical with that of Zerubbabel (The forty-six years mentioned in John 2:20 may be reckoned from 27 B.C., when the temple of Herod was begun till 28 A.D., when the words in question were spoken. But as the actual building of Herod only took ten years, and its completion by Herod Agrippa was long afterwards, there is some ground for the interpretation of Surenhusius [Mishna, v. 356] – that the forty-six years relates to the period of the building of Zerubbabel's Temple [536 B.C. to 459] with the intermissions of the work, on the theory that Herod's Temple was not to be recognized). Among the thousand wagons laden with stones, and ten thousand skilled artisans, there were a thousand priests trained as masons and carpenters who carried on their task dressed not in workmen's clothes, but disguised in their sacerdotal vestments – this idea of the sanctity of the undertaking took complete possession of the national mind; so much so that it was to have been accompanied by a preternatural intervention which had not been vouchsafed either to Solomon or Zerubbabel. It was said that during the whole time rain fell only in the night; each morning the wind blew, the clouds dispersed, the sun shone and the work proceeded.

The more sacred part of the interior sanctuary was finished in eighteen months. The vast surroundings took eight years, and, though additions continued to be made for at least an additional eighty years, it was sufficiently completed to be dedicated by Herod with ancient pomp. Three hundred oxen were sacrificed by the king himself, and many more by others. As usual, a day was chosen which should blend with an already existing solemnity, but on this occasion it was not the Feast of Tabernacles, but the anniversary of Herod's inauguration. The pride felt in it was as great as if it had been the work not of the hated Idumaean, but of a genuine Israelite. "He who has not seen the building of Herod has never seen a beautiful thing" (Hartwig Derenbourg, 154; Comp. John 2:20; Mark 13:2).

Let us look at this edifice and temper of Herod, so closely intertwined with the fall of the Old and the resurrection of the New Religion.

If not for the first time yet more distinctly than before, the great area was now divided into three courts.

The Outer Court

The first or outer court, which enclosed all the rest, was divided by balustrade's, on which was the double inscription in the two great Western languages forbidding the near approach of Gentiles. It was entered from the east through a cloister, which, from fragments of the first Temple cherished like the shafts of the old Temple of Minerva in the walls of the Athenian Acropolis, was called the cloister of Solomon (According to Josephus, this apparently had been left untouched by Herod and it was afterwards proposed to Herod Agrippa to restore it. But he also shrank from so serious an undertaking). Besides those relics of the antique past, the face of the surrounding cloisters also exhibited the more fantastic accumulations of the successive wars of the Jewish Princes – the shields, swords, and trappings of conquered tribes, down to the last trophies carried off by Herod from the Arabs of Petra (According to Josephus, it would seem that these took the place of the shields which adorned the porch of Solomon's Temple and the tower of his palace. Whether I Macc. 4:57 refers to the inner or outer front is not clear). Among these figured conspicuously (as a symbol of allegiance, not conquest) the golden eagle of Rome, the erection of which was Herod's latest public act (Josephus). The great entrance into the temple from the east was the gate of Susa – preserved, probably, in whole or in part, from the time of the Persian dominion.

The court itself must have been completely transformed. Its pavement was variegated as if with mosaics. Its walls were of white marble. Along its northern and southern sides was added the Royal Cloister, a magnificent colonnade of Corinthian pillars, longer by one hundred feet than the longest English Cathedral, and as broad as York Minster (According to Josephus, in general style, though not in detail, they resembled the contemporary columns of Baalbec or Palmyra, as may be seen by the remnants still preserved in the vaults of the Mosque). At the north-west corner was the old Asmonean fortress, founded by John Hyrcanus, but strengthened and embellished by Herod and in his manner called Antonia after his friend Antony. In this secure custody were always kept (with the exception of a few years in the reign of the Emperor Tiberius) the robes and paraphernalia of the High Priest, without which he could not assume or discharge the duties of his office, and the retention of which in that fortress marked in the most public and unmistakable form his subjection to the civil governor – Asmonean, Herodean, or Roman – who for the time controlled Jerusalem. Beneath the shade of this fortress, in the broad area of the court corresponding to the Forum or the Agora, were held all the public meetings at which the Priests addressed the people. It was surrounded by a low enclosure, over which the Priest could look towards the Mount of Olives.

The Inner Court

Within this Outer Court rose the huge castellated wall which enclosed the Temple. It had nine gateways, with towers fifty feet high. One of these on the north was, like Boabdil's gate at Granada, called after Jechoniah as that through which the last king of the house of David had passed out to the Babylonian exile.

Through this formidable barrier, the great entrance was by the Eastern gate – sometimes called Beautiful, sometimes, from the Syrian general or devotee of the Maccabaean age, Nicanor's gate (That there were only two great Eastern gates appears from the Mishna [Taanith, ii. 6]). The other gates were sheeted with gold or silver; the bronze of this one shone almost with an equal splendor.

Every evening it was carefully closed; twenty men were needed to roll its heavy doors and drive down into the rock its iron bolts and bars. It was regarded as the portcullis of the Divine Castle.

The Court of the Priests

On penetrating through this sacred entrance, a platform was entered called "of the Women." At the sides of this were the Treasuries. Thirteen receptacles of money were placed there like inverted trumpets. The women sat round in galleries as still in Jewish synagogues. It was here that on the Feast of Tabernacles took place the torchlight dance, and the brilliant illumination of the night (Mishna, Suca). It was a tradition that in this court none were allowed to sit except Priests or descendants of David.

From this platform the worshipper ascended by fifteen steps into the Court of the Priests. In the first part of it was the standing-place for the people to look at the sacrifices, divided from the rest by a rail. The chambers round this court were occupied by the Priestly guard, and contained the shambles for the slaughter of the victims. In the center was the altar, probably unchanged since the time of Judas Maccabaeus. In the south-east corner was the Gazith or "Chamber of the Squares", where sat the Great Council, with a door opening on the one side into the outer court, on the other into this inner precinct.

The Porch

Immediately beyond the altar was the Temple itself. Sacred as it was, this received various additions, either from the mighty Restorer or his immediate Asmonean predecessors. On the building itself a higher level was erected. It was encased with white marble studded with golden spikes (Josephus). The Porch now had two vast wings, and, in dimensions and proportions, was about the same size as the façade of Lincoln Cathedral.

In the Porch hung the colossal golden vine, the emblem of the Maccabaean period, resting on cedar beams and spreading its branches under the cornices of the porch, to which every pilgrim added a grape or a cluster in gold, till it almost broke down under its own weight (Mishna, Middoth). Later was added here the golden lamp presented by Helena, Queen of Adiabene.

The Sanctuary